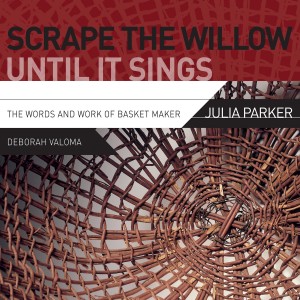

Just this fall, Scrape the Willow Until it Sings, the Words and Work of Julia Parker, was published locally by Heyday Press. Author Deborah Valoma is the Textile Department Chair at CCA in Oakland & San Francisco, and specializes in the history and theory of textiles. Scrape the Willow is an unusual mixture of academic treatise on the aesthetics and significance of basketry as historically and ideologically understood by archaeologists, anthropologists, and art historians, and Julia Parker’s down-to-earth account of her history, and personal transformation into an accomplished and influential Indian basket maker and Native American leader.

Just this fall, Scrape the Willow Until it Sings, the Words and Work of Julia Parker, was published locally by Heyday Press. Author Deborah Valoma is the Textile Department Chair at CCA in Oakland & San Francisco, and specializes in the history and theory of textiles. Scrape the Willow is an unusual mixture of academic treatise on the aesthetics and significance of basketry as historically and ideologically understood by archaeologists, anthropologists, and art historians, and Julia Parker’s down-to-earth account of her history, and personal transformation into an accomplished and influential Indian basket maker and Native American leader.

Julia’s own extensive and wonderful descriptions are used to describe how she understands and feels about basketry, beginning from her acquaintance with traditional Yosemite Miwok culture following her marriage, to the creation of her first baskets in her 30’s. She chronicles her quest to preserve the heritage of the California Native American basket makers by learning techniques, and cultural history, as well as traditional maintenance and preparation of the plant materials from Indian elders. Through Julia’s own words, we learn how she has sought to replicate lost techniques from preserved basket collections, exercise her artistic individuality, and work towards consciously documenting and passing on this evolving tradition to succeeding generations of the Parker family, and Indian basket makers of the California Indian Basketweavers Association (CIBA), an organization she helped found, and to non-Indians who have either taken basketry classes with her, or observed her during more than 50 years of weaving demonstrations at the Yosemite Museum in the National Park.

Most importantly, Julia helps us to understand the spiritually-based Native American perspective, with its respect and reverence for the plants utilized, as well as the centrality of baskets to a traditional way of life. This is a tall order, and Deborah Valoma carefully organizes the results of countless hours of interviews with Julia so that the oral narrative flows.

We are told about Julia’s remarkable life as she first came to learn about Native American culture as a young woman in one of only a few surviving Indian villages in California. Born in Graton, CA in 1929 to Coast Miwok/Kashaya Pomo farmworker parents, Julia and her siblings had no opportunity to learn much about their cultural roots before they were placed first in foster care in Santa Rosa, CA, and then sent to the Stewart Indian School in Nevada where Native American languages and cultures were forbidden. But following her school graduation, Julia married fellow student Ralph Parker, a Miwok/Paiute resident of Yosemite, whose grandmother Lucy Telles, was a master basket maker working at the Yosemite Museum as a “cultural interpreter.” Although Ms.Telles taught Julia about her utilitarian baskets , it was only after Lucy’s death that Julia made her first basket. In 1960, concerned that the only images her children were seeing of their culture were in “shoot ‘em up” Westerns, she approached a friend, the Chief Ranger Naturalist at Yosemite National Park, who suggested that she assume the vacant museum position, thus beginning a journey in basketry, and in explaining Native American culture to non-Indians, that Julia continues through today.

Professor Valoma’s treatise successfully integrates what she has learned from Ms. Parker into the milleniums long history of basketry, and the very recent academic debates about what was historically seen as “women’s work.” Even for non-academics, this is fascinating material– a concise compendium of intellectual thought regarding basketry.

For instance, Valoma discusses how, as a result of the lack of textile artifacts due to organic degradation, but also due to “interpretive biases in the male-dominated fields of archaeology, anthropology and paleontology…[which played] a decisive role in the assignment of scientific value”, basket making was largely devalued or ignored by scholars.( p. 113) It was only in the 1970’s, when gender biases were challenged, that the role of the “woman as gatherer” was reexamined, and given its proper due as the mainstay of prehistoric human nutrition, and women’s containers were understood as enabling “a revolutionary shift from foraging and eating on the spot… to collecting, transporting, storing and distributing foods” permitting a more stable economy, and encouraging sharing, social connections, and solidarity. Professor Valoma explains how women and fiber technology have been at the center of human cultural development–with the practices of Native American women of California at the time of Western contact in the mid-19th century supporting this assertion.(p. 116)

Scrape the Willow also provides enlightening information for those of us who have seen the extensive Native American basket exhibits in Northern California– at the Oakland Museum, Yosemite National Park Museum, Grace Hudson Museum (Ukiah), the Gatekeeper Museum (Tahoe City), and elsewhere.

As Professor Valoma notes. “traditional arts in general, and basketry in particular, has always been in a state of dynamic flux, “( p. 141) She provides the example of Yosemite valley in the early part of the 20th century, where “historical patterns of subsistence” had already been disrupted, partly due to Park regulations against hunting and gathering. Valoma suggests that basket making might well have vanished if Yosemite Valley and Mono Lake weavers had not experimented with new materials, patterns and scale for a burgeoning collector’s market that provided the women with needed income: “Innovative weavers responded nimbly to market forces by mining the aesthetic potential of coiled baskets (favoring these over twining) with an ever-escalating urge towards intricacy. Stitches became progressively more minute and densely packed… [and] basket makers intensified the complexity of their geometric compositions. Once relatively restrained, basket designs became increasingly animated, and virtuosity of surface design became the hallmark of the new genre.” (p. 28) “Basket makers were doing what they had always done: they crafted expressions of their reality with what was at hand. And baskets were what they had always been: tools of empowerment and survival. Weavers seized the moment to forward their tradition into a new era, the results were spectacular.”( p. 29)

This historical background is beautifully brought to life by Julia Parker’s remembrances of conversations with her Indian mentors , and the many accounts of how she utilized her artwork to non-confrontationally correct assumptions made about her culture by non-Indians.

Julia’s wonderful baskets and those of her mentors were recently on display in a special exhibition at the Yosemite Park Museum, Sharing Traditions: Celebrating Native Basketry Demonstrations in Yosemite 1929-1980, which ran through the end of October, 2013. More importantly, you can actually meet and speak to Ms. Parker most weekdays at the museum, as she continues to weave her baskets and amazing stories.

Scrape the Willow Till it Sings can be purchased directly from Heyday Press at www.heydaybooks.com