The Woman Who Became the Bayeux Tapestry:

An Interview with Mia Hansson

by Cathy Koos

All photos courtesy Mia Hansson

Self-professed, “a bit crazy” textile artist, storyteller, and illustrator, Mia Hansson began her early embroidery work literally at her Nan’s knee. Born in Sweden, Mia now makes her home outside London.

Back in 2001, Mia began doing Viking-age reenactments. When she found out no shops sold the garb, she decided to DIY her outfit. She thought she would “take two bits of fabric, stick them together and I’ll have a dress.” So, she laid the fabric on her kitchen floor, and “this is no lie, I rolled on my side, put a pin there and cut it and then cut another piece the same size, and voila, I made a two-man tent.” Eventually trusting her tape measure, she arrived at the Viking Valhalla village immensely proud of her dress.

Soon, friends, schools, museums and even a wedding party were asking for custom dresses and tunics. Alas, after a stormy night rounding up wayward pigs at a reenactment on the Isle of Man, Mia decided camp life was not for her.

Reenactment garb made way for smaller projects like caps, purses and glove puppets, but Mia found she wanted a project with a longer commitment as she is a full-time caregiver for her son. Recalling two tapestries she created that are now housed in Missouri that were images reminiscent of the Bayeux tapestry, Mia decided to explore a Bayeux reproduction.

Fast forward to 2005, a wrong turn error coming off the Calais ferry found Mia and her family in Normandy, France. The Bayeux tapestry was not their intended destination, but Mia’s husband thought it would be rude not to stop in to see it. And thus began the family’s lifelong captivation with this visual history.

The Tapestry.

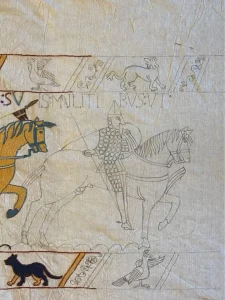

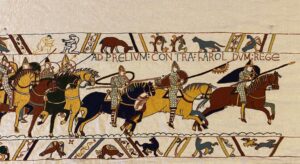

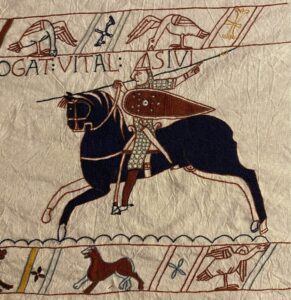

The Bayeux, while often referred to as a tapestry, is actually a story told in a 70-meters long narrative embroidery, not a traditional, woven, tapestry. Designated a “Memory of the World” by UNESCO, this valuable historical textile depicts conquest of England by William, Duke of Normandy in 1066, as well as insights into medieval life in Norman times. For a society that likely could not read, this allowed viewers to see their stories. The top and bottom edges depict daily life as well as once-in-a-lifetime events, like Halley’s comet. For more on the original Bayeux, see the next article.

Back to Mia’s tale.

On July 16, 2016, with her husband funding the reproduction project, Mia set off on a road trip in search of “feel good” linen from London’s fabric Mecca market on Goldhawk Road.

At one shop, she was invited into the basement, literally climbed a stack of linen bolts with a ladder, and found the perfect bolt.

Forty meters of washed linen later, Mia began what has now become her lifelong passion.

After seeing the original work in France, Mia found a book by David Mackenzie Wilson which photographically documents each segment in nearly full scale. By measuring the entire book with a tape measure and sharing that she is not mathematically endowed, she eventually found that 1.82 is the magic number to create her reproduction in full scale.

Using some amazing drawing pencils found in a backyard shed that were her father’s, Mia draws a panel at a time. While a woven tapestry artist uses a cartoon placed behind the loom, Mia draws directly on the linen.

Faithfully reproducing the original, Mia also reproduces some of the ancient errors and blames them on a seamstress she laughingly calls Mildred. She surmises that it was likely that four women (and possibly up to 32) at a time worked on the tapestry – two on each side of a very long, narrow table. This multiplicity of seamstresses is reflected in variations such as the color of the legs on King Edward’s throne – red stem stitch on one and yellow chain stitch on the other.

During the textile’s long history accidents happen, and repairs would have been made using colors slightly different from the original. And there is the assumption that multiple hands worked on it, so inconsistencies occurred.

The original work is mainly done in an outline stitch called Bayeux stitch, but Mia has found that stem stitch works better for her natural way of stitching. Variations in the twist and thickness of the original thread compared to what she can source today also makes for a slight difference in outlines and infill stitches. Likely the original seamstresses used stretching frames and could utilize both hands (one on top, one underneath), whereas Mia does not use a frame.

While Mia does not currently display the replica in public anymore, she has on special occasions, such as this:

On the original tapestry, there is a lot of text written in a fairly distinct font that telegraphs “old” to me. Mostly in Latin, it spells William several different ways, which reflects the literacy of the times, as well as the fluidity of the language, and changes colors often in the same phrase. Even some letters, like W, are stitched differently – sometimes as two V’s and sometimes overlapped as we write today.

Mia relates another story of stitching on the commuter train and ending up with her needle in the thigh of a gentleman opposite her. He said he was “glad” she did it because it allowed an opportunity for him to ask about her project. Oh my!

Another Nan lesson was to have as neat a backside as the front, which Mia keeps faithful. In the original tapestry, chins varied in random places, as well as stocking and garment colors.

She also finds some interesting attempts at depth of field. Medieval women likely did not know what the chaos of a real battle scene looked like, or war horses on a ship, so Mia supposes it’s “like medieval AI.” In the original, sometimes the number of legs does not actually match the number of horses shown.

During the Covid lockdown, a newspaper heard about Mia’s project and asked if they could photograph the in-progress work. They thought she and a friend could just stand in the road and hold it out socially distanced between them. However, at that point it was 27 meters long – fortunately Mia had lots of friends and masks and they eventually got it stretched out. As Mia’s husband says, “It’s blooming amazing!”

As an adjunct to the Bayeux project, Mia has a traveling glove puppet named Stella and you can follow Stella’s Adventures on Facebook. Mia also has both a Facebook group for the tapestry at Mia’s Bayeux Tapestry Story, and a website where you can read more. Her books are available on the website and Amazon. https://www.miasbayeuxstyleart.uk/

Stella on her latest adventure