Dyeing for Blue

Cathy Koos

Figure 1 Dye house ruins, WikiCommons

Seventeenth century religious and political oppression in the Palatinate region of Europe lured numerous highly skilled artisans to the colonies, especially to Penn’s Woods (Pennsylvania). William Penn’s land tract was particularly attractive to these refugees. It was a win-win situation for everyone – King James garnered exceedingly accomplished craftspeople and the craftspeople were welcomed to the colony with open arms. The Moravian church in Europe envisioned a self-sufficient community of young men and women as their “Second Sea Congregation,” whose mission was to bring and share their beliefs to America.

Weavers, woodworkers, farmers, and textile artisans arrived in about 1740 from the Palatinate, or Moravian region of what is now Central Europe, seeking toleration for their religious practices, bringing their much-needed skills with them. Communal living arrangements were quickly built while the farmers were working the lands and building up livestock. A meeting house and four other buildings were also constructed, one each to accommodate single men, single women, married couples, and children. Yes, apparently the children were raised away from their parents.

All the new arrivals to the colonies needed clothing, and the textile artisans were ready to fill that need. The Palatinate region had been growing flax for centuries and weaving it into linen.

These new immigrants were also known for their skill with blue dye, bringing both flax and woad seeds with them. Professional dyers were in demand, as immigration increased the need for linen. Woad was a poor man’s substitute for the more expensive indigo, and it was also easier to grow in the cooler climate. As a consequence, woad has proliferated throughout North America and even become invasive in Northern California.

Figure 2 Early wood cut of woad.

Dyeing in the Bethlehem area began as soon as the Moravian farmers produced their first harvest of linen and wool in 1742. Along with their food crops and sheep, the Moravians also grew woad, madder, and dyer’s weed for blue, red and yellow dyes. Forest products such as mushrooms, bark, nuts, and roots supplied browns and greens, along with much-needed tannin. While indigo needs a subtropical growing zone, woad was to go-to blue dye in the cool climates of Europe.

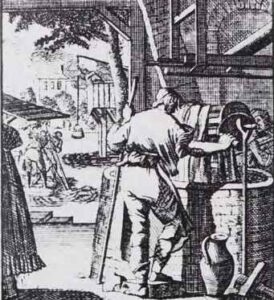

Once productivity grew, a separate dye house was constructed. Dyeing was a skill passed from master to apprentice, with Matthias Weiss’ arrival on the scene. Weiss subsequently passed the craft on to his son. Careful inventories reveal detailed records of equipment, as well as production. For instance, in 1758, the dye house had three copper kettles, a lead blue kettle, scales, axes, mallets, pestles, barrels for lye and rainwater, kettles to cook potash, and more.

Figure 3 Bethlehem dye house1

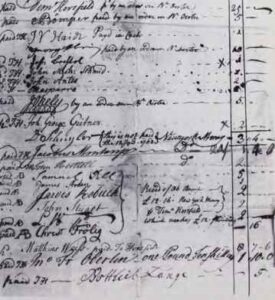

A destructive lightning fire in 1761 caused Weiss and twenty-two other citizens to pledge twenty pounds for the purchase of a fire engine. Another community was starting up in Salem, North Carolina and Weiss consulted with their textile workers there, bringing madder seeds. Salem was far enough south that indigo could thrive.

Figure 4 Fire wagon donations, Bethlehem1

Figure 5 Madder and Brazilwood, early wood cuts1

As happened often with communal living groups, capitalism soon won out and many of the textile artisans began producing goods for customers outside the community. With the increased customer base came profits and the ability to import indigo from the West Indies and Brazilwood from Brazil.

References

1Colby, Michael and Graves, Donald. “Pennsylvania Folklife Vol 36, No. 3” (Spring 1987). https://digitalcommons.ursinus.edu/pafolklifemag/116

Moravian Historical Society, Nazareth, PA

National Museum of Industrial Arts, Bethlehem, PA