The Mill Girls

Cathy Koos

My first career in the seventies to early nineties was in Silicon Valley with a now nonexistent high-tech company called Digital Equipment Corporation or DEC. Headquartered in a repurposed textile mill in suburban Boston, our accounts were mainly universities, governments, and defense contractors. Ever expanding outward, our Santa Clara office was an international anchor point to the west coast and Pacific Rim.

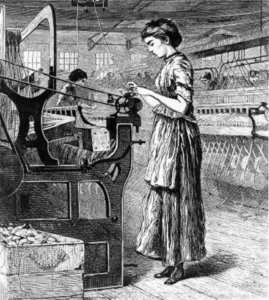

Figure 1 Mill Girls, nps.org

At the birth of DEC in 1965, mill buildings were cheap, available, and close to Boston. While the interiors were repurposed to offices and high-tech manufacturing, even the smelly old mill ponds and canals got some much-needed attention. Soon, the mills were no longer bustling with the noisy clack-clack of spinning machines and weaving looms but quietly humming along to a new industry. Instead of turning out yards of cloth, we were on the forefront of the computer age, turning out everything from chips to minicomputers. It was every DEC employee’s dream to get back to Maynard or Lowell for a tour of The Mill.

But let’s take a look back at the mill’s beginning. Maynard and Lowell were a brand-new type of town back in the early 1820s: the Company town. Company towns themselves are not new – coal mining patches had already sprung up to house and support the coal miners and their families. Originally the Assabet Woolen Mill and later the American Woolen Company, Maynard was a woolen mill town and Lowell produced cotton cloth with high production looms.

Instead of coal miners and their families, the textile industrial revolution spurred a need for a large workforce to meet the new demand for cheaply manufactured textiles. Working off the coal patch model, but assuming a labor force of single young women, the mill town was planned as a utopian environ, offering young farm girls a wage and a safe home with educational, social, and spiritual opportunities.

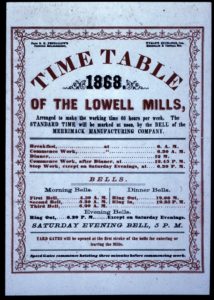

Figure 2, recruiting notice, nps.org

Francis Cabot Lowell, founder of the town and its namesake, saw a worldwide demand for finished cloth. He traveled to Great Britain in the early 1820s and toured textile mills. Some say he conducted industrial espionage by memorizing the design of the power looms. He also visited planned textile mill villages in Scotland, and he modeled Lowell after those communities.

Agricultural families were large, as the children offered a cheap, ready workforce for the farm. As the industrial revolution began, offspring were surviving childhood, due to better health and food supplies. But as the children grew up, the family farm could not be economically divided amongst all the surviving children. It was still a time of primogeniture for sons and not all the daughters could marry into another farm family. Thus, mill owners like Lowell were presented with a ready workforce from nearby farms.

Recruiting campaigns throughout New England reached young women in remote villages and farms. Procurement agents traveled from town to town, setting up shop to interview and sign contracts.

Figure 3, Lowell Mill timetable, nps.org

Another ready workforce came in the guise of male famine immigrants from Ireland. These men provided the heavy labor needed for construction of the canals and mill buildings.

Lowell acquired its cotton from the South, frequently returning the cheaper cotton cloth back to the South to clothe the enslaved people. This cheap coarse cloth was even known by the moniker of Lowell cloth. By 1845, profits averaged 25% a year and Lowell-made cloth was sold to customers all over America, as well as South America, China, Russia, and India.

War benefited most of the textile mills — the American Woolen Mill made Civil War era uniforms and many defunct mills were reactivated to make parachutes and other military necessities during World War II.

While the mill town planners did bring these young women a safe sense of freedom and economic support, many detractors felt that it was simply a new form of slavery with long hours and harsh working conditions sweetened by a small wage, room, and board. Mill owners wanted to avoid the negative reputation of mills in England, where destitute adults and small children worked under miserable conditions of long hours, poor food, disease, and unsanitary conditions.

Figure 4, Arlington Mills, Weave Room 2, nps.org

Referred to as operatives, there was an attempt to elevate the mill girls to a virtuous middle class akin to a schoolteacher. The operative’s lives were tightly regulated by the mill owners – both at work and during their time off. Contracts stipulated curfews and required the women to attend church. In exchange, they received salaries of $3-4 per week, unheard of wages for women anywhere in the country, with room and board costing about $1. However, men were still paid more for the same work. To sweeten the pot, cash wages, educational and spiritual opportunities were offered.

Twelve- to fourteen-hour workdays, six-day work weeks, and close chaperoning by the boarding house “keeper” ensured extraordinarily little opportunity to stray off the virtue path. By 1840, Lowell and surrounding areas saw eight thousand mill workers employed. Thousands of Irish fleeing famine in their homeland emigrated to the greater Boston area, further increasing, and diversifying the labor force.

While the American Textile History Museum closed its doors permanently in 2016, most of its collection was transferred to Cornell University Library. Check here for current status on accessing the collection https://guides.library.cornell.edu/athm

Mill workers did strike, and a number of walkouts led to some improvement in labor conditions. Eventually, most of these New England mills closed, and manufacturing has moved offshore, but these mills forever changed the architecture and culture of these New England towns.

Additional reading:

http://npshistory.com/publications/lowe/index.htm

https://www.nps.gov/lowe/planyourvisit/placestogo.htm

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Boott_Mills

http://reader.library.cornell.edu/docviewer/digital?id=hearth4400683#page/15/mode/1up