Unspun Stories of Silk

Words by Cathy Koos

(Unless otherwise noted, all photos by author)

Figure 1 HistoricBethlehem.org, N. Swolensky

It was the holiday season, complete with candles in every window and boughs of holly festooning historic doorways. “O Little Town of Bethlehem” was orbiting my mind as I drew near Smithsonian’s National Museum of Industrial Arts in … the big/little town of Bethlehem, Pennsylvania.

Three associated museums in Bethlehem guide visitors through the historic district, interpreting the silk industry: The Moravian Museum of Bethlehem, the Kemmerer Museum of Decorative Arts, and the National Museum of Industrial History.

Figure 2 silk skeins

Figure 3 Smithsonian’s Museum of Industrial Arts

Before the Lehigh River steel mills built steam locomotives and ships, this mill town and the Lehigh River were all about silk.

Even though I grew up within an easy drive of Bethlehem, I only associated the city with the rough grit and sulfur odors of a working steel town. But there was a whole other earlier history I knew nothing about, so I set out on a mission of discovery of the burgeoning Colonial-era industry of silk.

For millennia before European settlers arrived in the Lehigh Valley, the Delaware Lenape people called the area home. Coincidentally, they called the region Nolamattink, or “the place where the silkworms spring up…to spin their cocoons.” There are still Lenape speakers, so I am still researching whether that name was used pre-European contact or popped up as a consequence of the Moravian silk industry, but I will leave that for another day. There are a few native caterpillars that spin a cocoon similar to the Bombyx mori silkworm.

In 1609, King James of England encouraged mid-Atlantic colonists to abandon tobacco horticulture and move into sericulture, silk production. James provided the first cocoons from China, as well as white mulberry, Morus alba. The white mulberry was so prolific that it quickly spread and hybridized with the native red mulberry. Mulberry Mania soon gripped the region. Farmers and town-dwellers alike turned their hand to patches of mulberry trees and their attics into cocooneries.

Figure 4 Moravia overlay of contemporary Europe

Persecuted religious immigrants from Moravia (now a part of Czechia) arrived in America in 1735. By the early 1750s, a large Moravian community had settled in eastern Pennsylvania. Lewis von Schweinitz began researching native mushrooms in the region, later becoming the Father of American Mycology. However, fungiculture never promised to be a big money maker, so the Moravians turned their hand to silk. The Moravians brought with them textile production skills, as they were master weavers and spinners.

While looking for additional economic opportunities, Philipp Christian Bader noticed a prolific number of native red mulberry trees in the Bethlehem area. He built a cocoonery in the attic of the Single Brethren House and began experimenting with the Bombyx mori silkworms from China — raising and feeding them the local wild mulberry leaves, trialing the best way to boil the cocoons, and saving a select number of worms for the next generation. Once white mulberry was introduced, the silk industry really took off.

Figure 5 Silk worms and mulberry leaves in attic of Single Brothers House

Figure 6 Silk cocoons in attic of Single Brothers House

Figure 7 reproduction of cocoon boiling process

According to Bartram’s Garden in nearby Philadelphia, “Silk’s importance to the early modern economy cannot be understated. Elites in Europe had long preferred silk garb, leading Britain and France to develop highly profitable silk weaving industries by the early 1700s.”

Soon the unmarried women of Bethlehem’s Moravian community living in the Single Sisters House were processing and reeling cocoons into fine silk yarn, as well creating finished silk goods. It was here that George Washington purchased a fine pair of silk stockings for Martha in 1782 and “mulberry mania” hit the blossoming community.

Figure 8 Moravian spinning wheels

A dye house was soon erected, producing a special blue process developed by the Moravians in the Old Country. See another article in this issue on the blue dye industry.

While sericulture was never successful in the colonies further south like Jamestown, the Lehigh Valley became a global leader in silk production as silk became an important trade good throughout the world. According to the US Park Service, silk was usurped by tobacco in Virginia and the Carolinas for income and ease because slave trade in the South provided the labor, but silk thrived further north because of the Moravians.

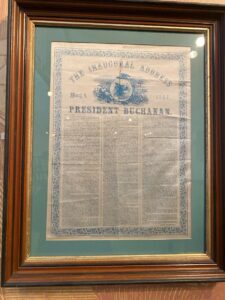

Locally made silk products displayed at the three museums ranged from silk stockings reputedly purchased by George Washington for Martha; a speech President Buchanan had printed on a silk scarf; on up through 20th century parachutes; dresses subsequently made from the parachutes; and ladies’ silk garments.

Figure 9 President Buchanan’s Inauguration speech, printed on silk

Figure 10 Victorian era dress

Winter blight in the mid-1800s proved a temporary setback, but the Lehigh Valley silk industry continued to import cocoons from China and Japan until Pearl Harbor in 1941.

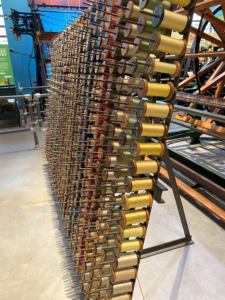

By the 1880s, spinning and weaving became more automated and several more mills arrived on the scene.

Figure 11 winder

Figure 12 warper

Figure 13 warper

Figure 14 Royle card punch

Figure 14 Royle card punch

Figure 15 Jacquard card lacer

Figure 16 silk spools

Figure 17 silk skeins

Figure 18 Jacquard loom

Figure 19 Docent describing Jacquard loom

Figure 20 mid 19th century silk purses

1919 saw the establishment of Laros Silk Industries and their focus was on ladies’ silk intimate wear.

Figure 21 Ladies silk slips, Laros Mill

World wars ushered the region into the steel age around 1900, diminishing the silk industry in necessary favor of ship building. With the build up to World War 2, most of the silk industry turned to parachute manufacturing and steel mills for warships.

Returning soldiers from World War II brought home their silk parachutes and war brides turned them into wedding gowns.

Figure 22 Parachute silk bridal gown, 1940s

Then acrylics and polyester textiles usurped the demand for silk in the last half of the 20th century. Times changed and the region’s genteel silk mills slipped away as steel mills took over.

The region continued to change and by the year 2000, even the mighty steel industry abandoned Bethlehem and shuttered its doors. The steel stacks stand rusting and abandoned, but the grand silk mills have become posh loft apartments – a fitting new chapter for a posh industry.