The Huguenots

Cathy Koos

More often than not, times of war cause vast movements of refugees fleeing loss of home and livelihood. We are seeing this situation unfold real-time with the war in Ukraine. Thousands of civilians stream relentlessly west–roller bags, children, and pets in tow. The refugees of Ukraine appear, not as your typical refugee of long, drawn-out conflict, but for the most part are clean and well-nourished, having had their lives quickly upturned in a matter of days.

figure 1 Ukraine refugees, npr.org

War and conflict usually come about from a small but significant handful of causes – territory, power, religion. The current Russian war against Ukraine is a war of territory. As rarely in past conflicts, for the most part these well-educated and skilled urban Ukrainian refugees are well-positioned to offer skills to the countries welcoming them in.

Now we cast our eye back in time to the time to another conflict, this time between Catholic France and the Huguenot Protestants in June of 1572, when Louis XIV set forth the Edict of Fontainbleau declaring one law, one religion, one king.

Named for their Swiss religious leader, Burger Bezanson Hugues, 70,000 Huguenot Protestants were subsequently murdered across France.

Figure 2 Edit of Nantes, Wikipedia

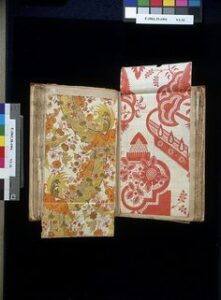

In their favor, the Huguenots had a skill to offer to a country offering their safe haven and England recognized that value. While English weavers excelled at fine woolens, the French surpassed in their ability to weave and drape the new blends of silk.

Huguenot Silk Weaving Sample Book, ca 1700. Pinterest

Queen Elizabeth I of England quickly understood that rather than import these costly textiles from France, they could simply invite the Huguenots to bring their skills and live in the safety of a protestant country where they would be free to ply their trade and build up Britain’s textile export trade.

Attracted to Canterbury, the bishop there even allowed one portion of the nave to be set aside for religious services in French, which continues to this day.

Figure 3 Huguenot Weavers Houses, Canterbury. Wikipedia

From Canterbury, many Huguenot weavers migrated to London and set up a weaving district near Petticoat Lane. The mass exodus of weavers from France compromised the numerous silk mills around Tours. Lacemakers flocked to the Midlands region as well as glassmakers, thus leaving France bereft of these skilled artisans and instead, enduring a brain drain which lasted many decades. In fact, in 1985 French President Francois Mitterand issued a formal worldwide apology to the Huguenot descendants.

Typical Huguenot Silk Weaving Loom, pinterest

By the early 1700s, Huguenots were also immigrating to America – specifically to New York, New Jersey, and eastern Pennsylvania – and later into the Piedmont region. Once in America, the Huguenots quickly assimilated into their new home, switching from French to English or Dutch and marrying into other settler families, and effectively losing their culture but not before sharing their vast textile skills.