Hidden Silk Weavers of Lyon

Cathy Koos

Hidden down an ancient passageway in old Lyon, France, lies the Soierie Saint Georges, one of the very last, original silk-weaving workshops. In a medieval town known as the capital of silk, this is where the French silk industry began.

Soierie Saint Georges

Silk weaving was birthed in 1536 when Francois 1st licensed Lyon as the sole silk center in France. By the census of 1788, we find an astonishing 14,777 silk looms in 5,832 workshops in the city of Lyon. In short order, the population had quickly jumped from 30,000 to 100,000. The busy workshops were located primarily in the ancient medieval quarter of the city, where the weavers lived above their brightly lit workshops.

At one time, over half the population of Lyon was involved in silk production. Silk producers were known as Canuts, given their moniker by the canette or bobbin. Their clients ranged from kings to the church, and even Napoleon’s army. Silk weavers were not simple workers. At a time when most of the population could not read, they were well-educated entrepreneurs and important movers and shakers in society.

Weavers revolt. Silk was sold throughout Europe using a middleman, so the Canuts didn’t really know the true value of their work. Extreme competition allowed merchants a disincentive to pay fair prices to the weavers.

Wikipedia

The early 1800s saw the Canuts ask for a minimum price agreement, but the king declined. This pushed the silk weavers into a series of fiery revolts in the early 1800s demanding fair prices for their silk.

Workers rebelled, closed their ateliers, and grabbed weapons from the town armory. However, the revolt was bloodily suppressed. The army was called up to quell the revolt, but only after several hundred workers were killed. The Canut’s motto was “Vivre en travaillant ou mourir en combatant,” (live working or die fighting) inspired other workers to rebel. By 1848, after three revolts, the agreement was finally accepted, and full-scale silk work peacefully resumed.

Drawlooms. Ever the innovators, drawlooms existed in China in the 10th century. The Italians co-opted and further refined the drawloom in the 1600s. The silk weavers of Lyon, the Canuts, soon embraced this technology, developed it even further, and created a strong niche in the luxury weaving market in early 17th century France.

Drawloom, Wikipedia

The Canuts were key to revolutionizing silk production, first using an Italian loom, the metier a la grande tire. In English, the draw loom. Although it required both a weaver and a draw boy to operate, this loom allowed a more mechanized method of pattern weaving.

1725 saw a great advancement in the automation of weaving when Basile Boucon introduced a continuous roll of paper with row of holes punched. Each row of holes equated to one row of weaving and drove the pattern repeat, thus preventing errors and creating consistency in the finished work. Like punched Braille cards, these rolls of paper “programmed” a particular pattern for the weaver.

Computer History Museum

Jacquard looms. When Joseph Marie Jacquard invented his namesake loom attachment in 1804, production of even more intricate patterns such as brocade and damask took off. No longer was the draw boy required to select and “draw up” specific heddles to create a pattern. The Jacquard attachment allowed even complex patterns.

Computer History Museum

Visitors Today

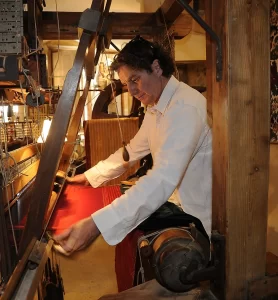

Roman de la Calle, https://www.soieriesaintgeorges.com/

Soierie Saint-Georges. Romain de la Calle operates the Soierie Saint-Georges, a silk workshop that dates to 1820. It is one of three remaining active workshops in Lyon. De la Calle took over the shop from his father and grandfather, and the atelier is open to the public. Romain weaves bespoke products for castle furnishings, tapestry, and for international orders.

Saint-Georges creates two products – a brocade which incorporates silver, silk, and gold. They also create velvets. Both techniques are quite time consuming with brocade producing 10 centimeters per day, while velvet only produces 5 to 7 centimeters per day.

La Soierie Vivante. In 1901, to safeguard the history of silk work in Lyon the Soierie Vivante was incorporated. They offer guided tours and demonstrations of the museum, as well as children’s programs. More information here: http://www.soierie-vivante.asso.fr/

National Museum of Scotland. For a working jacquard loom, visit here:

https://youtu.be/OlJns3fPItE?list=TLGGCw-9ud1KFOkyMjA0MjAyMw