Bedouin Weaving of Saudi Arabia is a recent publication by author, teacher and weaver Joy Hilden. It is a remarkable perspective of the Bedouin weaver, sharing insight into the lifestyle and changes that the culture, people and techniques have undergone from antiquity to the present. Recently I had the opportunity to correspond with Joy, and learn more about her life and journey. Conversation with Joy is a warm and empathetic exchange. She listens closely, paying attention to questions and comments, then providing thoughtful and illuminating responses. I believe this quality, as well as recognizing and embracing the opportunities in her life, are the foundations to her wonderful compilation of the Bedouin craft. What I wanted to learn was – what awakened her passion that led to writing the book? The answer lies in Joy’s background, and how exposure to Bedouin weaving influenced her life.

Outdoor Ground Loom

There is no lack of historical documentation of “how” a culture creates its cloth. Worldwide, modern practicing weavers are not silent. We help each other. We share our information and teach our craft. This sharing documents a foundation for new ideas and unpracticed applications. More importantly, sharing is another way to honor the roots of tradition so they do not become as ephemeral as the patterns of wind in desert sand. Joy discovered weaving as an adult, and through an opportunity that brought her back to her family’s roots, Joy immersed herself in the Bedouin weaving communities of Saudi Arabia. Love of the craft, and childhood memories of seeing the Bedouin weave, led to a resolve to share their story and document their craft. This story also brings attention to the stark reality of world power influence on the Bedouins lifestyle, and the craft we call our own.

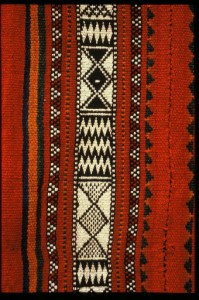

Bedouin Weaving Sample

The life of the Bedouin is built on a tradition of survival. Every activity has meaning and purpose – from the care of the animals and plants that produce the fiber, to the construction of utensils, clothing and the very walls within which the Bedouin live. It is a contrast in simplicity and complexity, and the products of their labor must be strong enough to protect from the harsh desert environment, yet soft enough to create a comfortable living style. Born in Palestine, Joy lived her first few years in Ramallah. Her mother was American, her father Palestinian – Quakers in a Christian Community. It was a time of the convergence of the British Mandate and World War II, which created a new era in the middle-east. In 1944 the family emigrated to America, crossing the ocean in Liberty ships. At first they settled in Mattapoisett, Massachusetts – on Buzzard’s Bay, where her father was appointed as a pastor. Soon afterward her father’s Palestinian and academic background enabled an opportunity to work for the Institute of Arab American Affairs (IAAA) in New York as a director. Although Joy had a strong sense of being American while in Ramallah, she felt more like a foreigner living in the United States. During the grammar school years, classmates were more curious and accepting of the foreign side of her roots. Closure of the IAAA in 1950 brought retirement for her father and the family moved to Whittier, California, where there was a large Quaker church. It was in Whittier that Joy completed high school.

During her years in high school, when it is important to feel like part of a group, Joy was most aware of having a different background – on both coasts. After a year and a half at UC Santa Barbara, she became ill, her father died, and she had to quit school. Not to be deterred, as her health improved, she applied for and won a scholarship to The San Francisco Art Institute, where she earned her Bachelor of Fine Arts degree. She married and spent more time on the East Coast. After divorcing, Joy ultimately settled in the San Francisco Bay area, where she taught art and raised her daughters, and married Robert Hilden. Weaving had made its introduction to Joy when she attended San Francisco State College for her teaching credential. In time, Robert received an opportunity to live in Saudi Arabia and teach English at King Fahd University of Petroleum and Minerals in Dhahran in 1982. By that time Joy’s two daughters were already grown and pursuing their own lives. The chance to live in an Arab country was an exciting prospect that could not be missed! And an academic schedule would allow Joy and Robert to visit back in the States during the summers, so they could keep up with friends and family while witnessing first hand transformations in the middle east as, over time, oil enforced its ubiquitous influence.

During the first several years they fell into the rhythm and pattern of university life. The campus itself was located next to an oil company, and there was much traffic from all corners of the globe. This made shopping and cooking an adventure in and of itself. With so many people from so many different cultures, there was an amazing supply of foods from abroad as well as the local produce. America, South America, Europe – all could be found in either a local market or their own Safeway! Ex-patriots, or expats (basically everyone not from the Saudi Arabian Kingdoms) mixed together or created their own little enclaves. At the same time, the government discouraged travel in the area or mingling with the locals. Domestic help was available for hire, but mostly came from other nations such as Thailand, the Philippines and Bangladesh. Some Palestinians performed household duties, and Yemenis could be hired for garden work.

Expats quickly learned to entertain themselves. Travel by women was limited to public transportation, taxi or private chauffeur, since, as is still the case today, it was illegal for women to drive. Longer trips required escort by a male relative who could act as a sponsor. Men were required to obtain permits for travel outside the immediate area. All men, as the caretakers of women, were held accountable for the actions of all their charges. In some cases this also meant the risk of being jailed. It was difficult for wives that wanted social and productive activities while their husbands were working or teaching. But that did not preclude the women from pulling together and forming clubs and guilds, exchanging skills, or planning events and trips for everyone, so there were many good memories.

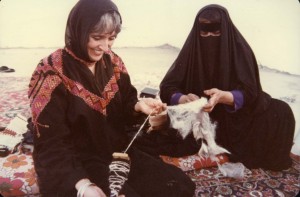

Joy getting a spinning lesson from Anik

Despite the hurdles, this was an active time for Joy. Joy helped found a guild in Saudi Arabia, and also shared her specialties of weaving, painting, printmaking, and drawing with the other expats. Of course, living close to the Bedouin population in Saudi Arabia rekindled Joy’s childhood memories of her father’s love for the Bedouin, and having seen the Bedouin weave near the family orange grove in Gaza. The Bedouin Saha weave is considered one of the most difficult pattern-making techniques. It is also called sahah, or shajarah weave. Joy had not learned this technique while in Saudi Arabia. But she did sign up for a Bedouin saha weaving class offered by Martha Stanley during one summer break in Berkeley, California. Martha had learned the technique the hard way – an associate had worked at reverse-engineering the methodology. Martha took on the task of documentation so she could teach it. (“The Bedouin Saha Weave and its Double Cloth Cousin”, In Celebration of the Curious Mind, Interweave Press, 1983). Now Joy not only learned the technique, but she also shared it with her weaving companions in Dhahran when back in Saudi Arabia.

One other major event occurred, however, before Joy was inspired to start her Bedouin weaving research. As luck would have it, Joy was able to get a job in nearby Damman as an announcer on an English-language television station which produced a documentary on Bedouin weaving. It was the springboard that made her local research possible since it introduced her to a Bedouin weaver who lived nearby.

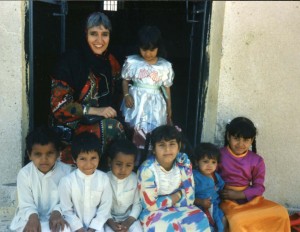

Joy with Ujman children near Nuayriyyah

Planning travel to the communities throughout the region was always a challenge, until Joy developed reliable contacts and support. The nomadic nature of the Bedouins made the research frustratingly slow, and yet provided her a perspective on the weaving process that only time could give. Bedouin women were generally pleased to share what they were doing with Joy. Not completely fluent in Arabic, communication was difficult at times because of the language and dialects across the regions. Joy’s ability to use the correct pronunciations, as well as being familiar with their craft, helped create an atmosphere of camaraderie.

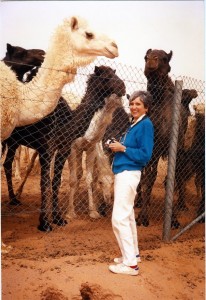

Joy and the camels at Hail Farm

Bedouin weavers are not always natural teachers. Learning came through observing a weaver at work – dependent upon the weaver’s project and at what stage the project was when Joy was able to arrange a visit. Observation of a certain project might take months, or sometimes years. After all, as was the custom with visiting family and friends within the Bedouin communities, you could visit and “hang out” – which meant staying for several days, or a week, or a month at a time. This certainly was a departure from our western practice of organizing a weaving, spinning or dying class for teaching purposes. Slowly, however, through word of mouth and other resources, Joy cultivated friendships with particular weavers. This way she could keep abreast of what they were working on at the time, and find out what was going on with their families and learn more about their work.

Joy’s words tell it best when describing how life in a middle-eastern nomadic community changed, and the things Bedouins needed to do to adapt their weaving to the changes. “In a true nomadic society, they had their certain routes that they took at certain seasons of the year. They would take a particular track, as it were, for centuries, back and forth and that would be considered that tribe’s territory. Going from nomadic to settled changed the economics of their world and introduced powers beyond their control. Before the introduction of the oil industry, traditional Bedouin uncertainties were natural events – such a drought (where their animals would starve or crops not grow), and attacks from other tribes (before Saudi Arabia was united). Drastic changes in recent times by the oil companies had been particularly unsettling for the Bedouin because their lifestyle is more fragile and more dependent on being able to be free to come and go and herd their animals and all those things. If your family is unsettled, you can’t produce.” In her book Joy quotes research by Dorr and Richardson (The Craft Heritage of Oman, 2003) which validates her observations: “Progress is a reality, not a choice; and crafts must adapt and remain relevant…A society should be able to broaden its horizons without forfeiting its past.” This reality was apparent in her interactions with the Bedouin weavers. Her empathy for their situation was key in Joy’s success in the many visits and interviews conducted during the remainder of her twelve (12) years in Saudi Arabia. Joy found, as in all cultures, that some people are capable of “remaining relevant” and some people are not. But she believes that it is also a social thing, not just an individual thing. Women learn from each other. For example, Joy states, “One particular weaver, Damtha, had the resourcefulness and positive outlook on things to survive. Not everyone is like that. Damtha could see how she could adapt her weaving techniques and output to changes in her environment successfully.”

Joy weaving on a ground loom at home

It is a testimony to her passion that Joy persevered and was not overwhelmed by the enormity of her task. Joy relates “When you think of it – Abraham had beit issha’ar – black tents – like the Bedouins have now. And how were those tents made? Women spun the yarn that was cultivated from their animals, and wove the fabric for the walls of the tents. This weaving has been around since the beginning of time.” Getting the information accurately on paper was not an easy task. Especially since the pressures of survival in a new world of technology and mass production discourage the current generation from maintaining this craft. Even some Bedouin who have been able to forestall complete sedentarization of their lives have opted to use mass produced materials such as pre-spun and/or dyed yarns and tent walls produced in city workshops. Settled Bedouins who make tent walls, potholders, storage bags, and other household items for sale to traditional Saudi Arabians, collectors and tourists also incorporate mass-produced material into their work. When asked about the introduction and use of synthetic and mass produced materials by some modern weavers, Joy responds “We have choices – and we have the best situation. And it depends on what you are making. If enough people know how to do this, there may be a time in this world that we will have to go back to doing it that way. We don’t know what is in store for this world. It’s crucial for the survival of mankind for there to be people who know how to do this stuff, craft skill, whatever – from scratch. Our era, where everything is mass produced, is such a teeny weeny dot on the history of the world. I don’t want our generation to be the one that let the knowledge die.”

Ironically, Joy teaches westerners about the Bedouin weaving techniques and its people, much in the same vein as her father taught Westerners about Arabian culture. But now it is many years from the days when Joy travelled on jawbreaking rocky roads, such as the ones to villages in the mountains near the Red Sea coast, in search of the information she has painstakingly documented. Living in Berkeley, California, there is no longer the requirement to wear an abayah (robe) or find a male sponsor to travel to or visit with other weavers. She still reminisces about visiting the desert markets of Nu‘airiyyah, and the homes of her Bedouin weaver friends. And another book is in progress. It will be a biography of her Palestinian father – a testament to Joy’s accomplishments which were ultimately made possible by her parents’ love and union.